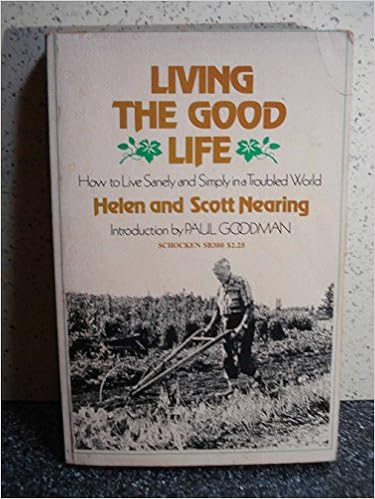

As my folks were doing a big cleanup of the house I grew up in, an old copy of Living The Good Life by Helen and Scott Nearing turned up. I had heard this book mentioned as a venerated bible of the 1970s, but had never actually read it, so I was interested to finally get to the source. In poking around on the internet after reading it, I came across a related memoir called Meanwhile, Next Door to the Good Life by Jean Hay Bright, who was invited (together with her husband at the time) by the Nearings to homestead as their neighbors on the Maine coast. This led me to another memoir, This Life is in Your Hands, by Melissa Coleman, daughter of Susan and Eliot Coleman, who were likewise invited by the Nearings to farm on their land. Eliot subsequently became a guru to the organic growing community in his own right.

Like Melissa, I grew up on an off-grid homestead in a then-remote corner of the coast of Maine, and soon after I entered into the island’s K-6 elementary school I understood that the way our family lived was unusual. But I knew that we were not alone in our unconventional habits; many of my parents’ friends also lived in funky home-built shelters, kept livestock, and grew vegetables, and some likewise lived without electricity. And as I read these books I was struck by the similarity, down to remarkably uncanny details, of their memories to the way I grew up, and I came to more fully understand that in my childhood I was unwittingly part of a significant cultural moment and movement. As a student of the energy and resource issues that motivated many people in the black-to-the-land generation, I’m interested in questions about the significance of the practices and habits of that era, what can be learned, and what it suggests about the future.

The Nearings were a couple from comfortable urban backgrounds who moved to rural Vermont to homestead in the 1930s, when their radical politics drove them from more conventional occupations. There they homesteaded, grew food, produced maple syrup and sugar as a cash crop, and cultivated an austere lifestyle and philosophy that they laid out in Living the Good Life, which was published in 1954. As the rural economy recovered from the Depression and WW2, and the New York City culture encroached on southern Vermont with skiing and vacation homes, the Nearings moved to the remote coast of eastern Maine. There they took up their habits in relative obscurity, until young people searching for alternative ways of life following the cultural upheaval of the 1960s discovered their book and began flocking to their homestead on Cape Rosier for knowledge and inspiration in the early 1970s. Eliot and Sue Coleman and Jean and her husband Keith were two of these couples whom the Nearings took a particular interest in, and they sold them plots of land to build and farm on.

One of the themes that emerges in Bright’s book is the significant gap between the Nearings’ idealistic prescription for organizing home economic and social life, and the reality of what actually works. The Nearings claimed that one could live well on four hours a day of ‘bread labor’ to earn or produce basic needs, four hours a day of artistic, cultural, or activist pursuits, and four hours of social engagement. They claimed to meet their economic and spiritual needs by following this plan, promoted it fervently, and scorned those who fell short in various ways (excessive participation in the cash economy, living on the proceeds from invested capital, eating meat, etc.) But Bright lays out a detailed case that the Nearings were essentially trustafarians – at various key points they received inheritances or other financial boosts that allowed them to buy large tracts of land, hire help, take shortcuts, and generally live much more comfortably would have been possible without that ready source of transfusion. As a particular example, when the Nearings moved from Vermont to Maine, high-bush blueberries replaced maple syrup as their notional ‘cash crop’, but she shows that the crop never broke even, let alone sustaining their lifestyle and allowing them to build a spacious stone house.

Bright’s book is not a hatchet job; she clearly had and has a lot of regard for the Nearings, but also the scars of a person who has attempted to live by following an idealized prescription, combined with a reporter’s nose for the real story. And I’m sympathetic to her instinct that it’s important to pay attention to the distinction between what is actually true and possible, and what people are motivated to believe is possible. Richard Feynman said something along the lines of ‘the first principle is that you must not fool yourself – and you are the easiest person to fool.’ The Nearings laid out a path that was attractive and salutary in its broad outlines, but deeply unrealistic in its details, and they had what is surely a natural human tendency to plaster over rather than expose and troubleshoot the places where reality fell short of the ideal. Bright’s book explores how their actions had profound impacts – both for better and for worse – on thousands, perhaps millions of people.

One of the most interesting aspects of both the Bright and Coleman books was the amazing degree of commonality in fine detail with how I grew up, three hours further west along the coast, including:

- Practical daily use of an antique Glenwood wood cookstove

- Drinking goat milk, and other people thinking goat milk was nasty

- Amateur goat obstetrics

- Trauma of butchering animals in the yard

- Racoons in the corn at night, wrangling of electric fences, and usually-futile attempts to shoot them in the dark

- Being the only kid in class with heavy whole-grain sandwiches, while the other kids have Hostess Twinkies

- Keeping a freezer on the porch of a neighbor in town who has electricity

- Concerns about a nuclear reactor uncomfortably close to home

- Newspaper reporters coming to write human interest stories about your family (I was too young to actually remember this, but the aluminum printing plate with a faded image of my mom cooking over a woodstove is still tacked to the wall in the back of the pole barn).

- The Tomten, and other children’s books that I have not come across elsewhere

These were among the quirkier resonances, but there were broader and more poignant ones as well. Bright’s conclusion is that it is possible to live a fulfilling life on the land, foregoing many of the conveniences of modern society, but that unless you have a trust fund, it’s not realistic to do it by working only four hours per day, and that it’s all but impossible to do it without materially participating in the cash economy. And so a related theme is how homesteaders find their craft and their place in that economy – for Eliot Coleman it was market gardening and related promotions, and for Bright and her husband Keith it was writing and carpentry respectively – exactly the same trades, as it happens, that my parents found for themselves.

A related question that preoccupies me at the interface of ecology, economy, and culture is the question of which back-to-the-land practices represent true advances from a sustainability and social progress perspective, and which are solely cultural badges. The Nearings were surely serious about ending war, alleviating social ills, and living in harmony with nature, and organizations like MOFGA were explicitly set up to change things. So it’s fair and important to ask whether they/we were on the right track with their prescriptions, and to what extent they’ve been effective.

Surely a nuanced view is appropriate here. Some of the cultural practices of that time (such as a whole-grains-based vegetarian diet) are surely improvements from an ecological perspective, a great number are surely neutral (e.g. the colors and patterns one chooses for their clothing), and a few are probably counterproductive (e.g. frequent trips to India in search of enlightenment). Rather than painting in broad strokes, it seems necessary to look at individual cases, consider realistic alternatives, and actually do the math. And to be effective, prescriptions must be socially as well as ecologically sustainable. Another word for subsistence is poverty; sustained, austere, backbreaking labor of the sort the Nearings advocated is not going to catch on broadly in a world where mechanized assistance is cheap and readily available. The Bright book is chock full of accounts of visitors who tried out the life and then went back to the city, and while some people (e.g. Eliot Coleman) find the hard work of farming viscerally compelling, most others (e.g. Jean Hay Bright) do not. Even those (like my family) who took to the back-to-the-land life gradually reintegrated themselves into the modern economy to a large extent, although many maintained back-to-the-land interests and cultural practices as well.

One thing that has struck me after attending the Commonground Fair off and on for close to 40 years, is how much of it is the same every year – the sheep dog demonstrations, the dry stone demonstrations, the spinning and weaving demonstrations, the draft horse demonstrations, the guy selling high-end Italian walking tractors, and so forth. The Fair is extremely valuable as a gathering place and a venue to meet old friends and affirm cultural affiliations, but how effective is it as a mechanism to drive real change? Forty years later, only a vanishingly small fraction of Mainers live off-grid (even though technology has made it quite comfortable), very few grow a meaningful amount of their own food, spinning and weaving are still oddities, virtually everyone still drives everywhere, and very few farmers are using horses for their tillage – and would we want them to? I’m wary of the tendency to turn sensible-sounding sustainability concepts like Local Food into talismans or cultural badges rather than theories that should be soberly assessed as possible means to a particular set of ends. As an example, I’ve calculated elsewhere on this blog that even fairly serious amateur gardening has only a marginal quantitative effect (even for the families that practice it), and speculated that it could be fairly easy to overwhelm any positive benefit by e.g. driving a truck repeatedly to a garden center for supplies. It’s not hard for me to imagine that the greatest quantitative benefit of home gardening might come not from direct effects on the carbon impact of their diets, but rather from capturing the attention of the gardeners and reducing their inclination to take long trips by air during the growing season.

Another resonant theme is the challenge of maintaining relationships through the challenges of hard work, personal discovery, and parenting – particularly among the freewheeling communities of vibrant young people attracted to the Good Life scene. With the exception of the Nearings, the couples at the center of both books grew apart and split up (perhaps hastened in the case of the Colemans by the tragic drowning death of their middle daughter in a farm pond). I remember this phenomenon likewise as one of those mysteries of the adult world as seen from kid height – how families that I knew as inseparable social units would suddenly spin apart, with fragments moving to far-flung places, and newly-wise children solemnly explaining custody arrangements. But despite the unconventional mores of the back-to-the land community, I have no reason to believe our families were any less permanent than those in the mainstream, and the question of why certain couples weather these challenges while others do not remains a mystery toward which these books can only offer particularly detailed singular case studies.

There’s a lot more that could be said, but in any case, I heartily recommend this three-generation sequence of books as a thought- and memory-provoking journey for anyone who lived or is interested in the 1970s back-to-the-land movement.